The fight against gender-based violence has often been cast as a women’s issue. However, successful programmes in Africa show the importance of engaging men and boys in the discussion.

As this year’s 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence draws to a close, it is disheartening to note that 27 years after the campaign launch, violence against women and girls continues unabated. According to UN Women, 1 in every 3 women worldwide experience physical or sexual violence in their lifetime. If it were a disease, it would have been called an epidemic.

Decades of fighting for a gender just society, particularly by women and women’s organizations, have achieved change. We have seen women activists at the frontlines with campaigns such as #MeToo, #HearMetoo, Time’s Up and, at the extreme, #MenAreTrash. We have also witnessed countries sign and endorse agreements committed to ending violence against women and girls, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. But while these initiatives place women at the centre of the issue, there is a new wave of programmes focused on prevention rather than response, putting men and boys at the heart of the discussion.

Africa provides a particularly illustrative example both of the problem of violence against women and of the innovative solutions that are creating change. Across Africa, women’s lives continue to be compromised and endangered, with a notable spike in recent years of cases of abductions, forced child marriages, rape and sexual abuse and threats, owing to religious fundamentalism, conflict and legacies of colonialism. In this context, new solutions are emerging.

MenCare are leading the way. Coordinated by the organizations Promundo and Sonke Gender Justice, they have since 2011 set up context-specific, targeted programmes that provide training for men and boys on violence-related issues. The mission of the campaign is to promote “men’s positive involvement in the lives of their partners and children as this creates a global opportunity for equality, and it benefits women, children, and men themselves”. The hallmarks of the campaign are improved maternal and child health, stronger and more equitable partner relations, a reduction in violence against women and children, and lifelong benefits for daughters and sons.

Campaigns in South Africa and Rwanda have achieved success by adapting this approach to the local context, focusing on fathers as engines of change. In South Africa, MenCare helps men live beyond the legacies of apartheid violence. More than 50 percent of children in the country grow up without their fathers. This absence has contributed to some boys looking for alternative sources of masculine identification and validation like gangs. As a result of this exposure, they grow up to become abusive, thereby contributing to high levels of abuse of women and girls in the home. On the other hand, girls grow up to accept domestic violence as the norm.

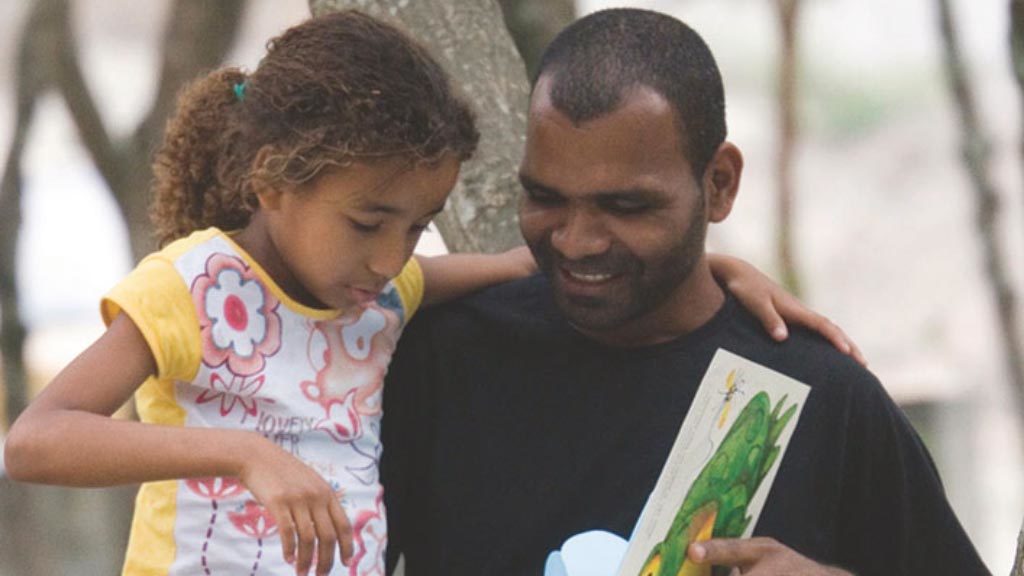

To combat this, MenCare’s campaign promotes the positive and active involvement of fathers in the lives of their partners and children. Their main tool is the provision of positive parenting classes of 12 weeks where participants (both male and female, though it is mainly the men) go through different modules learning how to deal with abuse they may have experienced earlier on in their lives and how to use non-violent ways in resolving conflict within and outside the home. Above all, participants learn what it is to be a positively-involved father, sharing care-work in the home. They are challenged to think about what kind of legacy they would want to leave behind for their children and family.

The participants of the programme are its biggest advocates. One father who participated said: “Violent behaviour came quick to me. Sometimes I would ask myself: ‘Why?’ But I think it was stress; sometimes you are not going to work but need to provide for the family.” He recalls that he would shout at his wife for no reason, admitting that the presence of a crying baby only made things worse. During the training, he asked himself, “Why am I doing this to my children? I wanted to change to be a role model for my kids; you must break the cycle of violence because your child will learn from you.”

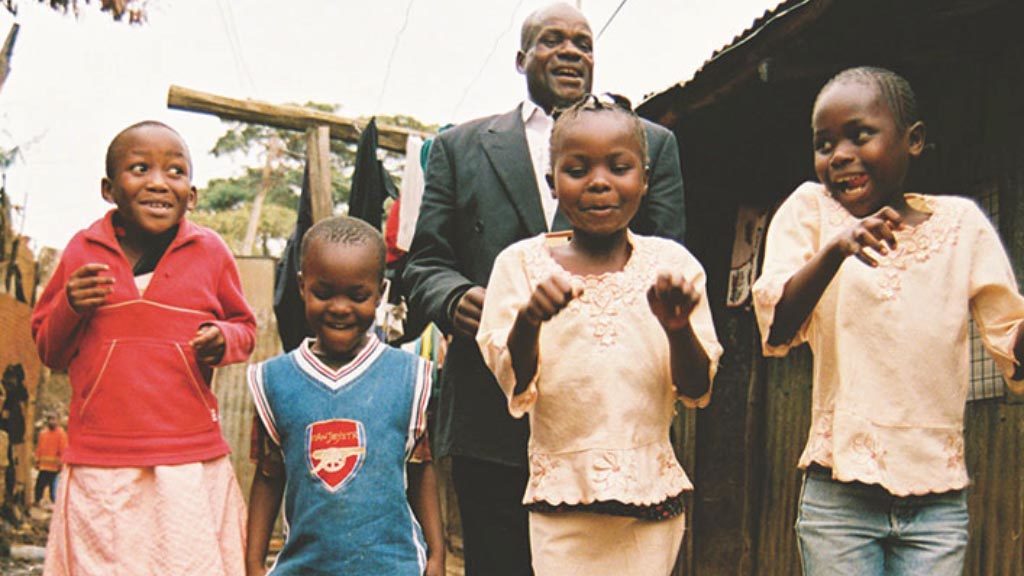

In Rwanda, the effects of gender-based violence are well-known. The country is still tackling the legacy of the 1994 genocide, in which violence was clearly gendered: men formed the majority of the 800,000 deaths, while 500,000 women suffered sexual violence. Out of this tragedy, a more equal society has emerged, driven by higher female participation in politics and the workforce. However, 34% of women are still estimated to have experienced intimate partner violence.

Similar to the campaign in South Africa, a programme developed by MenCare in 2015 sought to reduce violence by providing counselling and education for expectant fathers. Two years later, they found that levels of domestic violence among participants were 44% lower than the national average. The focus of the training? Simply providing a forum for men to gather with their peers and have an open and frank discussion about topics such as pregnancy, communication, and sharing caregiving responsibilities.

MenCare falls under the umbrella of Promundo, an organisation set up in Brazil in 1997 which now operates on a global scale to promote a new kind of masculinity. One of its latest programmes, ‘Manhood 2.0’, has responded to the #MeToo movement by harnessing the power of open discussion, using arts-based therapy, role-playing, and peer-to-peer conversations to deconstruct harmful gender norms among young men in the US. Such programmes do not represent a shift from ‘victim-blaming’ to ‘man-blaming’; they are recognition that men, too, suffer from rigid, restrictive gender roles.

We live in a world that has a paradoxical view of violence. Society often projects violence on the one hand as a necessary – even positive, heroic – force in the context of war and security, but on the other hand as a negative, destructive force in the domestic sphere. Faced with two conflicting images, men are tasked with striking a balance between the two. The continued prevalence of violence against women and girls shows that, all too often, the balance cannot be sustained. Campaigns such as MenCare are essential to redefine the relationship between violence and masculinity, and in doing so create a productive role for men in ending gender-based violence.

With thanks to participants of the FUF seminar on gender-based violence, who inspired some of the discussion points in this article.