The large numbers of displaced populations we see today have been responded to with overall regressive measures. Matthew Scott, an international lawyer specializing in migration, talked to us about the possibilities and challenges of displacement in the context of disasters and climate change that lie ahead.

Matthew Scott is an international lawyer at the Raoul Wallenberg Institute who focuses on migration in the context of disaster and climate change. He explains the challenges with the current legal framework under which refugees are addressed.

– The idea of a ‘climate refugee’ does not readily fit within the requirements of the refugee definition under the UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which defines the status and the rights of refugees, says Scott. This is because it is difficult to pinpoint climate change as the single cause of migration. Climate change can rather be understood as a risk amplifier – gradually deteriorating livelihoods.

– A toolkit approach that can address the diverse forms of displacement in the context of disasters and climate change is therefore necessary, Scott stresses. In addition to the UN Convention, we need complementary protection mechanisms, such as the European Convention of Human Rights, and contextual policies that address specific conditions in particular regions or sub-regions. It is also important to highlight that most displaced people either move to neighbouring countries or stay within their home country. Hence, action with a focus on internal displacement is called for.

Matthew Scott shares some positive trends on migration and adaptation strategies. For instance, New Zealand is discussing the possibility of a ‘climate refugee’ visa for people in their immediate neighbourhood, whose livelihoods are challenged as a result of climate change. This is an example of orderly migration – meaning that migration is used as an adaptation to climate change rather than as a last exit.

– Mobility as a strategy enables people to move with dignity, Scott emphasises.

Even if this would require a new governance system that puts conditions on states regarding migration, Scott remains cynical to this kind of realisation:

– States are unlikely to adopt new international obligations that go against their perceived economic and political interests in a world that is still very state-centric.

He views the current global trends as proving this point, taking Brexit as an example.

Migration entails economic and cultural benefits. Nevertheless, states often focus on the short-term socio-economic pressures that the large influx of migrants result in. There is also a strong narrative of national security today that plays to people’s fears, Matthew Scott follows.

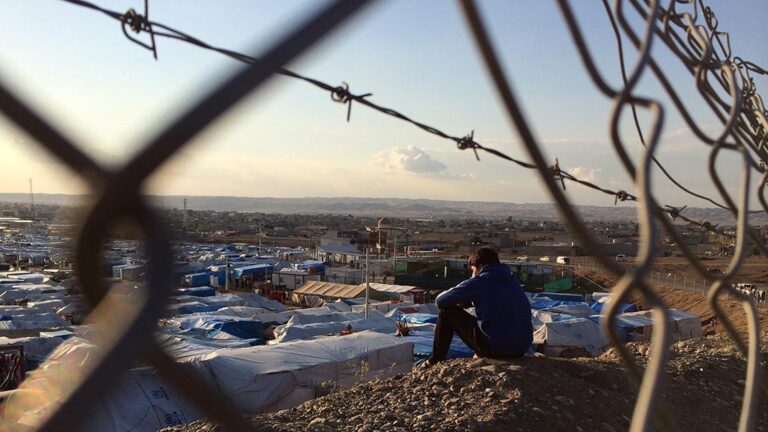

– People are scared of both climate change and of migration, of large volumes of people that cannot be controlled. This fear leads us to think “how can we stop this?”, instead of “how can we use a nuanced toolkit that includes a human rights-based approach?”. The ultimate response becomes force and increased border security.

Scott speculates that climate change could be the key cross-border challenge that makes states willing to cooperate. But how much damage that needs to be done before states will act beyond their short-term national interests, is an answer only future can tell.