Laws that prohibit the sex industry perpetuate gender-based violence. That is the opinion of Chantell Martin and Cameron Cox from the Sex Workers Outreach Project, SWOP, Australia.

The International Day to end Violence against Sex Workers takes place on the 17th of December every year. This day is to remind us how discrimination often stemming from laws against sex workers can perpetuate and even legitimise violence. The international day of activism was initiated following the trial against American serial killer Gary Ridgway, known as the Green River Killer, in 2003. Many of Ridgway’s victims were sex workers, his explanation for this being that he “knew they would not be reported missing right away and might never be reported. I picked prostitutes because I thought I could kill as many of them as I wanted without getting caught”.

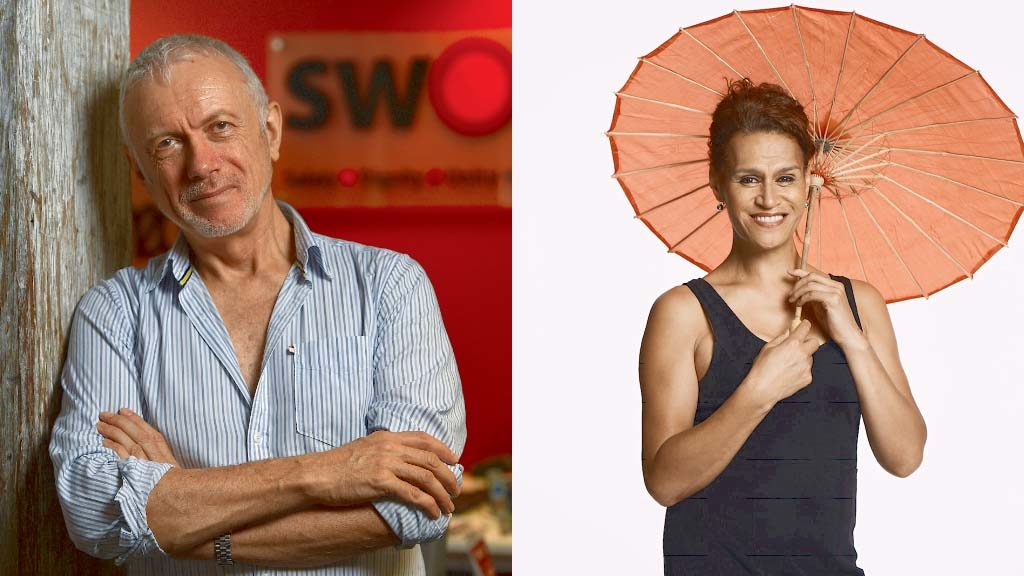

We spoke to Chantell Martin and Cameron Cox from SWOP (Sex Workers Outreach Project) Australia, a peer sex worker organisation. Both have a long history in sex work as well as contact with thousands of sex workers every year. They both made their concerns clear when discussing gender-based violence.

Chantell and Cameron agree that, like in all other industries, the vast majority of violence in the sex industry is perpetrated by cis men against cis women and trans women. However, unique to sex work they highlight, “it is the stigma and discrimination of sex work that often legitimises and perpetuates violence”. Cameron continues to explain:

– Sex workers still face discrimination which impacts their access to health care, access to a safe workplace and access to protection under the law. […] It’s well known that sex workers are less likely to report violence against them because it outs them to start with. It’s also less likely that the crime will be investigated and that the crime will receive proper punishment.

Cameron speaks of the sex offender Adrian Ernest Bayley, who raped five sex workers in Melbourne, Victoria. Lenient sentencing relating to these offences meant Bayley could sexually assault and murder another woman named Jill Meagher in 2012. Jill’s husband, Tom Meagher, said at the time: “I’m aware that his previous victims […] were sex workers, and I’ll never be convinced that doesn’t have something to do with the lenience of his sentence”. Tom Meagher was right; it was only following this case that consent laws were changed in Victoria to ensure sentencing of sexual assault irrespective of the occupation of the complainant.

– Sex workers are not only discriminated against in the law but also in its implementation, Cameron points out.

According to Cameron and Chantell, laws often reflect a belief that sex workers shouldn’t exist. They argue that models of full criminalisation of sex work as exists in Croatia or partial criminalisation as in Sweden do not serve or protect sex workers. And while there is little evidence that these laws reduce sex work, they do push sex work underground where sex workers are more likely to provide riskier services such as working in isolated areas.

Chantell makes it clear what she would like to see for sex workers.

– The decriminalisation of sex work around the world. This would implement a major shift for all sex workers towards our human rights, sex worker rights, legal rights, and allowing better access to health for sex workers. Here in New South Wales [Australia] there has been decriminalisation for over twenty years and has proved that decriminalisation of the sex industry is the world’s best practice.