With the production and handling of sensitive data, humanitarian organisations could be risking the lives of the very people they’re mandated to protect. Yet, they might not even realize it until it is too late.

United Nations investigators have accused the Myanmar army of ‘genocidal intent’ and ethnic cleansing. Still, the Rohingya people continue to flee ongoing violence and persecution on the basis of their ethnic identity from Myanmar, crossing the border into Bangladesh.

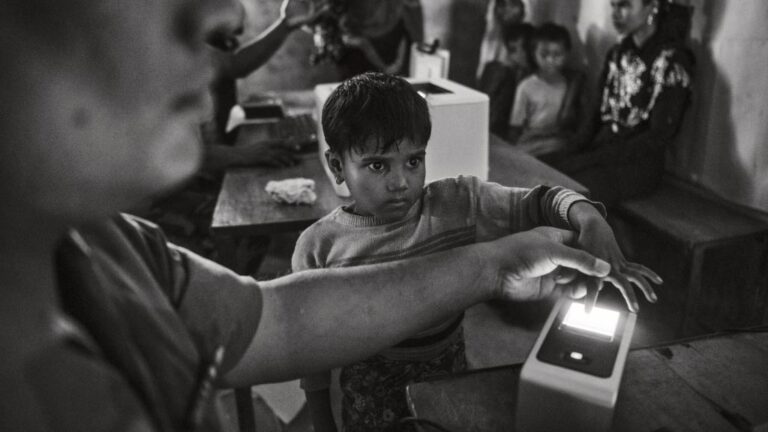

Today over 900,000 Rohingyas reside in Bangladeshi refugee camps seeking safety. In an attempt to provide services to this vulnerable population more efficiently, humanitarian organisations in collaboration with Bangladeshi authorities have been using biometric identification. However, with protests up roaring in these camps, Rohingya refugees now fear that this data may be used against them.

The term “biometrics” refers to characteristics usable for automatic recognition such as fingerprints, retinal patterns, facial structures and DNA. Although this might make work easier for humanitarian organisations, it also poses several risks such as violation of privacy, misidentification, stigmatisation of refugees and the misuse of data.

Currently, Rohingya identities in the form of biometrics are being collected and stored in a database in which they have no control over. Just last year it was confirmed that at least 8,000 Rohingya recorded identities have been shared with the Myanmar government during the negotiations with Bangladeshi authorities sending Rohingya back to Myanmar. Strikingly, however, there was no consultation in their willingness to return to Myanmar or consent before sharing the biodata with the very authorities they had fled from. Human Rights groups have responded by voicing their concerns that there is no effective plan in place to monitor or ensure the Rohingya’s safety if they return.

The Bangladeshi government has said explicitly that they don’t want the Rohingya, so one could only imagine what they could do with a biometric database of the Rohingya population. Sending the Rohingya, and all their data, back to Myanmar places their lives in huge peril and certainly undermines their safety and welfare. Although biometrics is useful in making the provision of services easier and efficient for humanitarian services, it is evident that it might come at the cost of the protection and safety of the very people that need it most.

For the agencies charged with protecting some of the world’s most vulnerable people, this case also raises a deep dilemma – Is collecting biometric data always in the best interests of refugees themselves?