In the midst of Sudan’s civil war, grassroot groups have taken on major responsibilities, such as distributing food and coordinating evacuations – as well as formulating a shared vision of a democratic future. To ensure this, global actors must work with Sudan’s civil society, writes Associate Professor Maha Bashri.

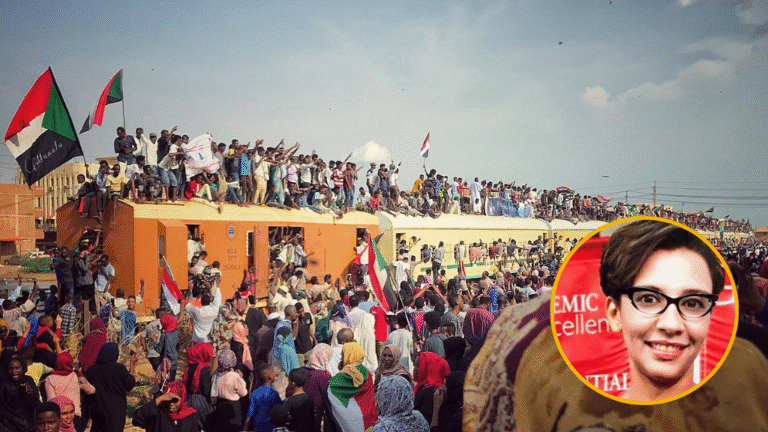

Sudan is collapsing, but not everywhere. In the rubble of a failed transition and an ongoing civil war, grassroots actors are keeping parts of society alive. In 2018, Sudan experienced a major political rupture. Mass protests across the country, led by professional unions, youth, and neighborhood-based organizing groups, ended the 30-year rule of President Omar al-Bashir. The uprising generated cautious hope that Sudan might finally transition from authoritarianism to democratic civilian rule. But five years later, the country is mired in a devastating civil war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

The conflict, which began in April 2023, has displaced over 8 million people, and more than half the population (over 25 million) now depends on humanitarian assistance, according to United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). In spite of the scale of the crisis, Sudan has struggled to attract sustained global attention. Media coverage has been minimal, and international diplomatic efforts have so far failed to secure a lasting ceasefire.

When the state fails, grassroots step up

This neglect obscures a critical story: in the absence of a functioning state, grassroots networks – also called Resistance Committees – have stepped into the vacuum. The Resistance Committees emerged during the 2018–2019 protests as local, horizontal networks organised at neighbourhood level.

Initially focused on mobilising protests, these groups have since evolved into critical actors in Sudan’s ongoing crisis. During the war, many Resistance Committees have taken on responsibilities that would normally fall to local authorities: distributing food, coordinating evacuations, repairing electricity and water infrastructure, and maintaining communication systems. Their actions illustrate a broader truth: governance does not disappear in collapse, it shifts.

Sudan’s current crisis is rooted in decades of military dominance. Since independence in 1956, repeated coups and short-lived civilian governments have eroded public trust. Even during nominal democratic periods, the military retained control over security and economic domains. Hopes raised by the 2018 revolution were quickly dashed, first by a flawed civilian-military power-sharing deal in 2019, then by the 2021 coup that dissolved the civilian cabinet, and finally by the outbreak of full-scale war in 2023, triggered by power struggles between the SAF and RSF over control of the security apparatus.

What sets this moment apart is the evolution of the Resistance Committees. Their significance lies not only in service provision. Throughout 2022, Resistance Committees in different regions developed political charters, culminating in the Revolutionary Charter for the Establishment of People’s Authority. This document articulates a vision of decentralized, inclusive governance that moves away from elite power-sharing agreements and instead centers local democratic participation.

Looking Ahead: How the civil society can shape the possibilities of the future

The Committees’ decision to remain independent from both the SAF and RSF has shaped their legitimacy among many civilians. Unlike past opposition groups, they reject military engagement and call for a fully civilian transition, reflecting deep skepticism of top-down politics and a commitment to bottom-up legitimacy. Yet, they face severe constraints: limited resources, constant risk, and exclusion from formal peace processes. Still, their persistence challenges prevailing notions of political authority and raises crucial questions about Sudan’s future governance.

Sudan’s crisis is often viewed through war and diplomacy, obscuring the grassroots governance sustaining the country. In the absence of state institutions, local networks, especially the Resistance Committees, are not only averting humanitarian collapse but also shaping visions for recovery and reconstruction. Central to the 2018 uprising, they remain vital yet excluded from formal peace efforts and largely ignored by the international community. This must change. Recognition demands more than awareness – it requires real support and engagement. If Sudan’s future is to be inclusive and accountable, global actors must work with those already rebuilding from the ground up.

Mer läsning om Sudan:

Ett år av krig i Sudan: ”En kris som får för lite internationell uppmärksamhet”